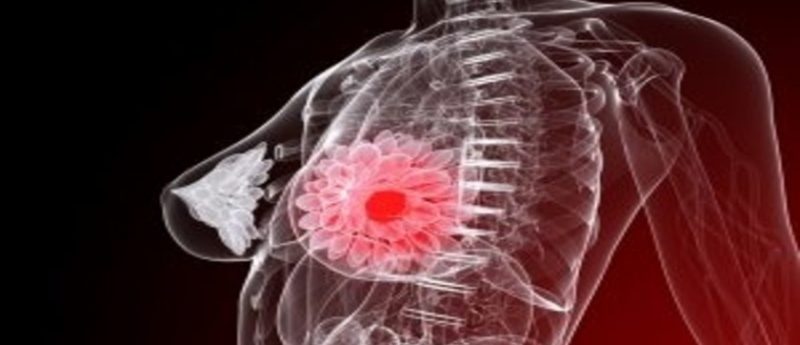

One in three with PALB2 mutation at risk of breast cancer by age 70

A team of researchers led by the University of Cambridge (UK) and the International PALB2 Interest Group have published findings in the New England Journal of Medicine that demonstrate that women with mutations in the PALB2 gene have a one in three chance of developing breast cancer by the age of 70. After BRCA1/2 genes, this makes the rare PALB2 gene mutation the second highest breast cancer risk factor.

It is well established that women with loss-of-function mutations in the PALB2 gene are known to have a predisposition to breast cancer. The lifelong risk of breast cancer in carriers with PALB2 mutations however had not been determined prior to recent study.

In the study, researchers across 17 international centers analyzed data from 362 individuals from 154 families without BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations who carried a PALB2 mutation. Scientists then used modified segregation-analysis to estimate the age-related risk.

Of the women with PALB2 mutations, there was found to be a 35% chance of developing breast cancer by the age of 70. However, these results were dependent on family history, with individuals having a much higher risk when other family members had also developed breast cancer. The absolute risk was found to range from 33% in female carriers with no family history, to 58% in carriers with immediate family members who had breast cancer.

Women with the PALB2 mutations who were born more recently were found to have a higher chance of developing breast cancer compared with older individuals. Carriers who were less than 40 years of age had 9 times the risk of developing breast cancer compared with the general population, while carriers older than 60 had 5 times the risk. Researchers have suggested that this may be due to a number of factors, including women having children at a later age as well as better diagnosis methods in recent years.

The PALB2 mutation was first linked to breast cancer in 2007 when it was demonstrated to interact with BRAC1/2 genes. Marc Tischkowitz of the Department of Medical Genetics at the University of Cambridge (UK), leader of the study, commented: “Since the BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations were discovered in the mid-90s, no other genes of similar importance have been found and the consensus in the scientific community if more exist we would have found them by now. PALB2 is a potential candidate to be ‘BRCA3‘.

“Now that we have identified this gene, we are in a position to provide genetic counseling and advice. If a woman is found to carry this mutation, we would recommend additional surveillance, such as MRI breast screening,” Tischkowitz continued.

PALB2-related breast cancer diagnosis methods are already being trialed and implemented within the UK. A new PALB2 clinical test has been developed by researchers at Addenbrooke’s Hospital, part of Cambridge University NHS Hospitals Trust, with the hope of being integrated into the NHS service. Other groups of researchers have suggested that PARP inhibitor drugs may be a potential therapeutic for PALB2-related breast cancer.

As a rare mutation, researchers including Tischkowitz believe that more studies are needed to identify the percentage of the population that carry the mutation.

The findings suggest that the breast cancer risk for PALB2-mutation carriers may be similar to the risk for BRCA2 mutation carriers. Thus, international collaborations following on from this study could aid future predictions of breast cancer and assist better diagnosis.

Breast cancer remains an area of novel research and as Peter Johnson, Cancer Research UK’s chief clinician, emphasizes: “We’re learning all the time about the different factors that may influence a woman’s chances of developing breast cancer.”

This study was funded by the European Research Council, Cancer Research UK and multiple other international sources.