Organoids as a model system in oncology: an interview with David Tuveson

Photo credit: CSHL

At the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Annual Meeting (March 29–April 3, Atlanta, GA, USA) we had the chance to speak with David Tuveson from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (NY, USA) about how organoids are being used to are being used to advance basic and translational cancer research.

Can you give us a brief overview of the session you chaired that explored organoids as a model system in oncology?

We had a session at AACR focused on organoids, four different speakers on four different topics, the first one was Yu Chen, from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (NY, USA) who talked about making organoid models of prostate cancer using genetically engineered mice and using patient-derived tumor samples. Yu showed that you can genetically edit mouse organoids to the point where you can make any version of the cancer model and implant that back into the mouse and glean fundamental insights into prostate cancer biology. He then showed that you could use the human organoids to test various therapies and thereby learn about new medicines that you could use for patients in general or for the specific patient the organoid was made from.

The next speaker was Michael Shen, from Columbia University (NY, USA) who made a variation of organoids for bladder cancer. And his method does not use the traditional ENR (EGF-Noggin-RSpondin) media of the Cleavers Laboratory but rather a modification. Dr. Shen was able to study different versions of human bladder cancer, learn things about the development of intratumoral heterogeneity in these specimens, and also look at new therapeutic options.

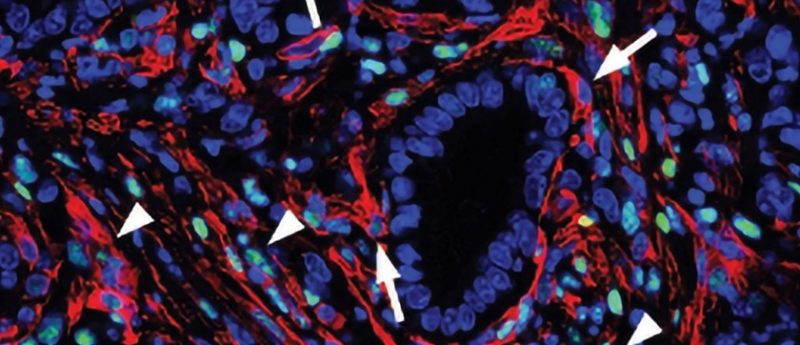

Third, Calvin Kuo, from Stanford University (CA, USA) talked about a variation of the organoid methods where he used air liquid interfaces to culture human cancer specimens in such a manner that you can study not just the cancer cells but also the micro environment cells including immune cells and fibroblasts. With these specimens, Calvin’s group was able to interrogate immunotherapies that gave great insights into the response of patients with a variety of cancer types.

Finally, the work I presented was focused on pancreatic cancer using classic organoid methods and showing that these methods could be used to identify groups of pancreatic cancer patients who were particularly susceptible to different types of chemotherapy that we used in the clinic. And how with this information, and we could stratify the patients and develop a signature of response and a pharmaco typing approach we are now using to design clinical studies.

Could you tell us about some of the advantages of using organoids in cancer research?

The major advantage of using organoids to study human cancer is that the methods are fast, such that you can develop an organoid in days or weeks. The amount of tissue needed to develop an organoid is small, and a needle biopsy that is readily obtained during clinical management is oftentimes sufficient. And so far the information we are receiving from the organoid appears to be in small numbers of patients, somewhat predictive of how they actually do when they are, for example, treated with the same drugs we use in organoid cultures.

What are some of the challenges of using organoids?

The challenges of using organoids are several. We need a method that is 100% successful and currently when we obtain these biopsies in our laboratory, regarding pancreatic cancer we are about 70% successful. You can’t tell a patient that unfortunately you are in the 30 percentile and we can’t help you, we have to have a method that works for all patients. So, we have to improve the efficiency of the method.

Second, we need a method that is fast enough to give a result in a week, so we can go from a tissue biopsy to a result a doctor can use in a week. You would have to get the sample, process it, grow the cells in whichever manner, evaluate various therapies and take that back to a patient. We have to increase the efficiency and decrease the amount of time it takes to get an answer.

In what ways do you think we could overcome these challenges?

Regarding the success of growing an organoid, decreasing the time from viable tumor tissue removal and transport to the laboratory should increase our ability to generate organoid cultures. Of course there could be certain molecular subtypes of cancer that don’t culture well, and the community is exploring this possibility.

The second topic is that of speed of culture development, and I think the speed will increase as we miniaturize the process, meaning instead of lumps of tissues that are processed into different petri dishes where we would then grow them, perhaps we could device more mobile engineering type approaches, nanotechnology type approaches, such as microfluidics where you have little tubes that, for example, you have an organoid in them that you would then pass a concentration readying of drug across and learn does it work or not. I do think that there is going to be innovative methods that will come out from the work of many people, that will, I suspect, work on both of these aspects.

One thing I should say is that if a patient has been treated recently with chemotherapy or radiation, it is sometimes very difficult to grow the sample because the therapy is used to kill cancer cells. That’s a reality of the system.

What cancer indications do you think are best suited to studying organoids?

I think any carcinoma should be thought of for this sort of research because that’s where at least the organoid have been best developed to date. The tumors where we have less to offer patients like pancreas cancer, ovarian cancer, small cell lung cancer; these would certainly be the indications where you would want to develop these approaches because if we need to find better therapies for such patients, I just suspect it’s potentially going to be useful for every patient who has cancer, that’s the opportunity. Some challenges currently exist, but it’s an opportunity that will teach us a lot about cancer as a scientific problem and help improve the medical approaches for every patient.

What would be your highlight from the 2019 AACR Annual Meeting?

If I had to pick one, I would say the highlight this year is related to the highlight last year, which is the continued impressive results from the immuno-oncology approaches. That’s where again the organoids are now showing utility with Calvin Kuo’s experiments where we can use slices of tissue, the T-cells in that tissue reflect the T-cells that are in the body of that patient, they can survive for 2 months in the organoid if they are incubated with the right growth factors and cytokines and it’s possible that we might have an organoid or tissue slice approach that would predict the right immunotherapies for patients going forward.

Is there anything else you are going to add?

People should read about organoids and consider using them in their research and their medical considerations. Organoids might be a new path forward, it might be the bacteriology test for cancer.

Profile: David Tuveson’s group is located at Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory (NY, USA) and the Lustgarten Foundation, where they use murine and human models of pancreatic cancer to explore the fundamental biology of malignancy and thereby identify new diagnostic and treatment strategies. The lab’s approaches run the gamut from designing new model systems of disease to developing new therapeutic and diagnostic approaches for rapid evaluation in preclinical and clinical settings. The lab’s studies make use of organoid cultures—three-dimensional cultures of normal or cancerous epithelia—as ex vivo models to probe cancer biology.